Edward Watkin on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sir Edward William Watkin, 1st Baronet (26 September 1819 – 13 April 1901) was a British

Watkin was born in

Watkin was born in

Watkin began to show an interest in railways and in 1845 he took on the secretaryship of the

Watkin began to show an interest in railways and in 1845 he took on the secretaryship of the

Watkin's last project was the construction of a large iron tower, called

Watkin's last project was the construction of a large iron tower, called

Watkin lived at Rose Hill, a large house in

Watkin lived at Rose Hill, a large house in Biographical details of managers, chairmen, etc

/ref> and Member of Parliament for the Great Grimsby constituency in 1877. A daughter, Harriette Sayer Watkin, was born in 1850. Mary Watkin died on 8 March 1888. After four years a widower, Watkin married Ann Ingram, widow of

Member of Parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members of ...

and railway entrepreneur. He was an ambitious visionary, and presided over large-scale railway engineering

Railway engineering is a multi-faceted engineering discipline dealing with the design, construction and operation of all types of rail transport systems. It encompasses a wide range of engineering disciplines, including civil engineering, compu ...

projects to fulfil his business aspirations, eventually rising to become chairman of nine different British railway companies.

Among his more notable projects were: his expansion of the Metropolitan Railway

The Metropolitan Railway (also known as the Met) was a passenger and goods railway that served London from 1863 to 1933, its main line heading north-west from the capital's financial heart in the City to what were to become the Middlesex su ...

, part of today's London Underground

The London Underground (also known simply as the Underground or by its nickname the Tube) is a rapid transit system serving Greater London and some parts of the adjacent ceremonial counties of England, counties of Buckinghamshire, Essex and He ...

; the construction of the Great Central Main Line

The Great Central Main Line (GCML), also known as the London Extension of the Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway (MS&LR), is a former railway line in the United Kingdom. The line was opened in 1899 and built by the Great Central Railw ...

, a purpose-built high-speed railway line; the creation of a pleasure garden with a partially constructed iron tower at Wembley

Wembley () is a large suburbIn British English, "suburb" often refers to the secondary urban centres of a city. Wembley is not a suburb in the American sense, i.e. a single-family residential area outside of the city itself. in north-west Londo ...

; and a failed attempt to dig a Channel Tunnel

The Channel Tunnel (french: Tunnel sous la Manche), also known as the Chunnel, is a railway tunnel that connects Folkestone (Kent, England, UK) with Coquelles ( Hauts-de-France, France) beneath the English Channel at the Strait of Dover. ...

under the English Channel

The English Channel, "The Sleeve"; nrf, la Maunche, "The Sleeve" (Cotentinais) or ( Jèrriais), (Guernésiais), "The Channel"; br, Mor Breizh, "Sea of Brittany"; cy, Môr Udd, "Lord's Sea"; kw, Mor Bretannek, "British Sea"; nl, Het Kana ...

to connect his railway empire to the French rail network.

Early life

Watkin was born in

Watkin was born in Salford

Salford () is a city and the largest settlement in the City of Salford metropolitan borough in Greater Manchester, England. In 2011, Salford had a population of 103,886. It is also the second and only other city in the metropolitan county afte ...

, Lancashire, the son of wealthy cotton merchant Absalom Watkin

Absalom Watkin (1787–1861), was an English social and political reformer, an anti corn law campaigner, and a member of Manchester's ''Little Circle'' that was key in passing the Reform Act 1832.

Early life

Absalom Watkin was born in London t ...

,. After a private education, Watkin worked in his father's mill business. Watkin's father was closely involved in the Anti-Corn Law League

The Anti-Corn Law League was a successful political movement in Great Britain aimed at the abolition of the unpopular Corn Laws, which protected landowners’ interests by levying taxes on imported wheat, thus raising the price of bread at a tim ...

, and Edward soon joined him, rising to become a key League organiser in Manchester. Through this work, Watkin gained the friendship of the Radical leader Richard Cobden

Richard Cobden (3 June 1804 – 2 April 1865) was an English Radical and Liberal politician, manufacturer, and a campaigner for free trade and peace. He was associated with the Anti-Corn Law League and the Cobden–Chevalier Treaty.

As a young ...

, with whom he remained in contact for the rest of Cobden's life.

From 1839 to 1840 Watkin was one of the directors of the Manchester Athenaeum

The Athenaeum in Princess Street Manchester, England, now part of Manchester Art Gallery, was originally a club built for the Manchester Athenaeum, a society for the "advancement and diffusion of knowledge", in 1837. The society, founded in 1 ...

. In 1843 he wrote a pamphlet entitled "A Plea for Public Parks" and was involved in a committee which successfully sought the provision of parks in Manchester and Salford. He also took a prominent role in the Saturday Half-holiday Movement. In 1845, Watkin co-founded the ''Manchester Examiner

The ''Manchester Examiner'' was a newspaper based in Manchester, England, that was founded around 1845–1846. Initially intended as an organ to promote the idea of Manchester Liberalism, a decline in its later years led to a takeover by a group w ...

'', by which time he had become a partner in his father's business.

Railways

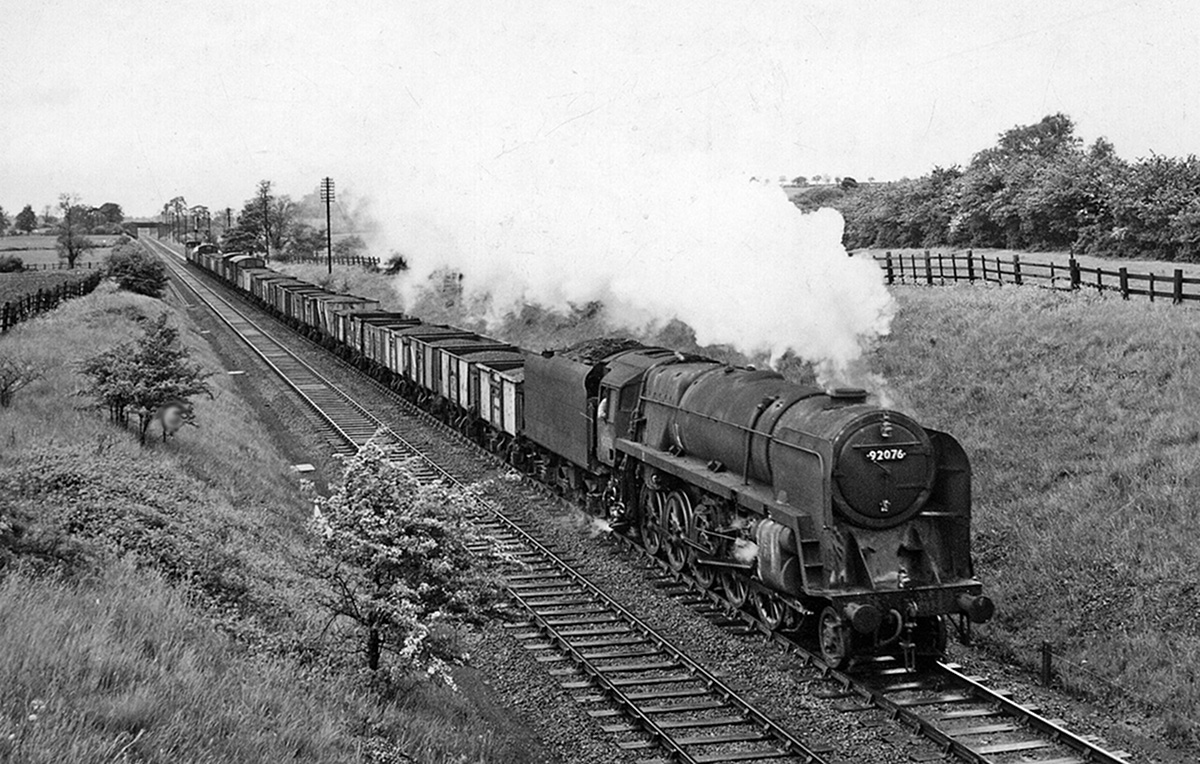

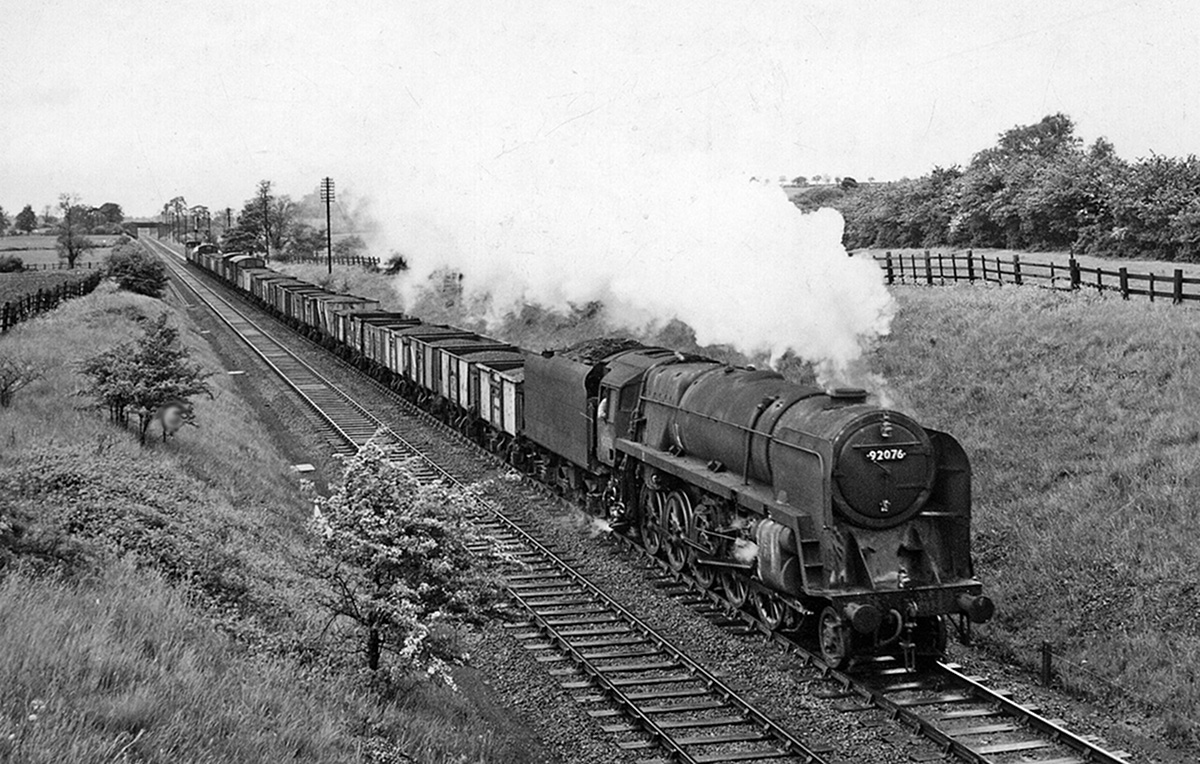

Watkin began to show an interest in railways and in 1845 he took on the secretaryship of the

Watkin began to show an interest in railways and in 1845 he took on the secretaryship of the Trent Valley Railway

The Trent Valley line is a railway line between Rugby and Stafford in England, forming part of the West Coast Main Line. It is named after the River Trent which it follows. The line was built to provide a direct route from London to North Wes ...

, which was sold the following year to the London and North Western Railway

The London and North Western Railway (LNWR, L&NWR) was a British railway company between 1846 and 1922. In the late 19th century, the L&NWR was the largest joint stock company in the United Kingdom.

In 1923, it became a constituent of the Lo ...

(LNWR), for £438,000. He then became assistant to Captain Mark Huish, general manager of the LNWR. He visited USA and Canada and in 1852 he published a book about the railways in these countries. Back in Great Britain he was appointed secretary of the Worcester and Hereford Railway

The Worcester and Hereford Railway started the construction of a standard gauge railway between the two cities in 1858. It had needed the financial assistance of larger concerns, chiefly the Oxford, Worcester and Wolverhampton Railway, and the New ...

.

In January 1854 he became the general manager of the Manchester Sheffield & Lincolnshire Railway

The Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway (MS&LR) was formed in 1847 when the Sheffield, Ashton-under-Lyne and Manchester Railway joined with authorised but unbuilt railway companies, forming a proposed network from Manchester to Grimsby ...

(MS&LR), a position held until 1861. In 1863 he was persuaded to return as a director of the company and shortly afterward became chairman, holding the position from 1864 to 1894. He was knight

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of knighthood by a head of state (including the Pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church or the country, especially in a military capacity. Knighthood finds origins in the Gr ...

ed in 1868 and made a baronet

A baronet ( or ; abbreviated Bart or Bt) or the female equivalent, a baronetess (, , or ; abbreviation Btss), is the holder of a baronetcy, a hereditary title awarded by the British Crown. The title of baronet is mentioned as early as the 14th ...

in 1880.

Manager from 1858, then president 1862–69, of the Grand Trunk Railway

The Grand Trunk Railway (; french: Grand Tronc) was a railway system that operated in the Canadian provinces of Quebec and Ontario and in the American states of Connecticut, Maine, Michigan, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Vermont. The rai ...

of eastern Canada, he promoted the Intercolonial Railway

The Intercolonial Railway of Canada , also referred to as the Intercolonial Railway (ICR), was a historic Canadian railway that operated from 1872 to 1918, when it became part of Canadian National Railways. As the railway was also completely o ...

, which eventually connected Halifax with the GTR system in Quebec

Quebec ( ; )According to the Canadian government, ''Québec'' (with the acute accent) is the official name in Canadian French and ''Quebec'' (without the accent) is the province's official name in Canadian English is one of the thirtee ...

. His grand vision was a transcontinental railway lying largely within Canada, but owing to the sparse population west of Lake Superior

Lake Superior in central North America is the largest freshwater lake in the world by surface areaThe Caspian Sea is the largest lake, but is saline, not freshwater. and the third-largest by volume, holding 10% of the world's surface fresh wa ...

, the scheme could not be profitable in the absence of government financial backing. Opposition to the idea within the company led to Watkin's ouster. The GTR would later miss various opportunities to build a viable Canadian transcontinental railway.

Abroad, he helped to build the Athens–Piraeus Electric Railways

The Athens–Piraeus Electric Railways ( el, Ηλεκτρικοί Σιδηρόδρομοι Αθηνών Πειραιώς, Ilektrikoi Sidirodromoi Athinon Peiraios, translit-std=ISO, ), commonly abbreviated as ISAP, was a company which operated th ...

, advised on the Indian Railways

Indian Railways (IR) is a statutory body under the ownership of Ministry of Railways, Government of India that operates India's national railway system. It manages the fourth largest national railway system in the world by size, with a tot ...

and organised transport in the Belgian Congo

The Belgian Congo (french: Congo belge, ; nl, Belgisch-Congo) was a Belgian colony in Central Africa from 1908 until independence in 1960. The former colony adopted its present name, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), in 1964.

Colo ...

.

Watkin was involved with other railway companies. In 1866 he became a director of the Great Western Railway

The Great Western Railway (GWR) was a British railway company that linked London with the southwest, west and West Midlands of England and most of Wales. It was founded in 1833, received its enabling Act of Parliament on 31 August 1835 and ran ...

and in January 1868 the Great Eastern Railway

The Great Eastern Railway (GER) was a pre-grouping British railway company, whose main line linked London Liverpool Street to Norwich and which had other lines through East Anglia. The company was grouped into the London and North Eastern R ...

. In fact it was Watkin who recommended Robert Cecil, who is credited with leading the GER out of its financial crisis. Watkin resigned as a director of the GER in August 1872.

By 1881 he was a director of nine railways and trustee of a tenth. These included the Cheshire Lines Committee

The Cheshire Lines Committee (CLC) was formed in the 1860s and became the second-largest joint railway in Great Britain. The committee, which was often styled the Cheshire Lines Railway, operated of track in the then counties of Lancashire a ...

, the East London

East or Orient is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from west and is the direction from which the Sun rises on the Earth.

Etymology

As in other languages, the word is formed from the f ...

, the Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire, the Manchester, South Junction & Altrincham, the Metropolitan, the Oldham, Ashton & Guide Bridge, the Sheffield & Midland Joint, the South Eastern, the Wigan Junction and the New York, Lake Erie and Western railways.

He was instrumental in the creation of the MS&LR's 'London Extension', Sheffield to Marylebone, the Great Central Main Line

The Great Central Main Line (GCML), also known as the London Extension of the Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway (MS&LR), is a former railway line in the United Kingdom. The line was opened in 1899 and built by the Great Central Railw ...

, opened in 1899.

Channel tunnel

For Watkin, opening an independent route to London was crucial for the long-term survival and development of the MS&LR, but it was also one part of a grander scheme: a line from Manchester to Paris. His chairmanships of the South Eastern Railway, the Metropolitan Railway, in addition to the MS&LR meant that he controlled railways from England's south coast ports, through London and (with the London Extension) through the Midlands to the industrial cities of the North; he was also on the board of theChemin de Fer du Nord The Chemins de fer du Nord''French locomotive built in 1846''

, a French railway company based in Calais

Calais ( , , traditionally , ) is a port city in the Pas-de-Calais department, of which it is a subprefecture. Although Calais is by far the largest city in Pas-de-Calais, the department's prefecture is its third-largest city of Arras. Th ...

. Watkin's ambitious plan was to develop a railway route which could carry passenger trains directly from Liverpool

Liverpool is a city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the 10th largest English district by population and its metropolitan area is the fifth largest in the United Kingdom, with a popul ...

and Manchester to Paris, crossing from Britain to France via a tunnel under the English Channel. The Great Central Railway's main line to London was also built to a comparatively generous structure gauge

A structure gauge, also called the minimum clearance outline, is a diagram or physical structure that sets limits to the extent that bridges, tunnels and other infrastructure can encroach on rail vehicles. It specifies the height and width of pl ...

, but contrary to popular belief it was not built to a 'continental' gauge, not least because there were no agreed dimensions for such a gauge until the Berne Gauge Convention was signed in 1912. Healy mentions two bridges which were built to "unusual dimensions ... to provide for possible widenings in case the Channel Tunnel project ever took off ..."

Watkin started his tunnel works with the South Eastern Railway in 1880–81. Digging began at Shakespeare Cliff

Shakespeare Cliff Halt is a private halt station on the South Eastern Main Line. It is located to the western end of the dual bore Shakespeare Cliff tunnel on the South Eastern Main Line to Folkestone, England. It never appeared in any pub ...

between Folkestone

Folkestone ( ) is a port town on the English Channel, in Kent, south-east England. The town lies on the southern edge of the North Downs at a valley between two cliffs. It was an important harbour and shipping port for most of the 19th and 20t ...

and Dover

Dover () is a town and major ferry port in Kent, South East England. It faces France across the Strait of Dover, the narrowest part of the English Channel at from Cap Gris Nez in France. It lies south-east of Canterbury and east of Maidstone ...

and reached a length of . The project was highly controversial and fears grew of the tunnel being used as a route for a possible French invasion of Great Britain; notable opponents of the project were the War Office Scientific Committee, Lord Wolseley and Prince George, Duke of Cambridge

Prince George, Duke of Cambridge (George William Frederick Charles; 26 March 1819 – 17 March 1904) was a member of the British royal family, a grandson of King George III and cousin of Queen Victoria. The Duke was an army officer by professio ...

;

Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until Death and state funeral of Queen Victoria, her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 21 ...

reportedly found the tunnel scheme "objectionable". Watkin was skilled at public relations

Public relations (PR) is the practice of managing and disseminating information from an individual or an organization (such as a business, government agency, or a nonprofit organization) to the public in order to influence their perception. P ...

and attempted to garner political support for his project, inviting such high-profile guests as the Prince

A prince is a male ruler (ranked below a king, grand prince, and grand duke) or a male member of a monarch's or former monarch's family. ''Prince'' is also a title of nobility (often highest), often hereditary, in some European states. Th ...

and Princess of Wales

Princess of Wales (Welsh: ''Tywysoges Cymru'') is a courtesy title used since the 14th century by the wife of the heir apparent to the English and later British throne. The current title-holder is Catherine (née Middleton).

The title was firs ...

, Liberal Party Leader William Gladstone and the Archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Canterbury. The current archbishop is Justi ...

to submarine champagne receptions in the tunnel. In spite of his attempts at winning support, his tunnel project was blocked by parliament, then cancelled in the interests of national security. The original entrance to Watkin's tunnel works remains in the cliff face but is now closed for safety reasons.

Wembley Park and Watkin's Tower

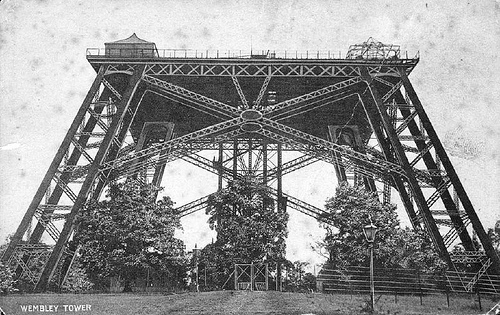

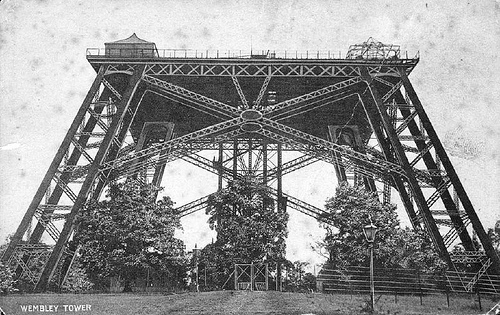

Watkin's last project was the construction of a large iron tower, called

Watkin's last project was the construction of a large iron tower, called Watkin's Tower

Watkin's Tower was a partially completed iron lattice tower in Wembley Park, London, England (then in Middlesex). Its construction was an ambitious project to create a -high visitor attraction in Wembley Park to the north of the city, led by the r ...

, in Wembley Park

Wembley Park is a district of the London Borough of Brent, England. It is roughly centred on Bridge Road, a mile northeast of Wembley town centre and northwest from Charing Cross.

The name Wembley Park refers to the area that, at its broade ...

, north-west London. The tower was to be the centrepiece of a large public amusement park

An amusement park is a park that features various attractions, such as rides and games, as well as other events for entertainment purposes. A theme park is a type of amusement park that bases its structures and attractions around a central ...

which he opened in May 1894 to attract London passengers onto his Metropolitan Railway. The park was served by Wembley Park station

Wembley () is a large suburbIn British English, "suburb" often refers to the secondary urban centres of a city. Wembley is not a suburb in the American sense, i.e. a single-family residential area outside of the city itself. in north-west Londo ...

, which officially opened in the same month, though it had in fact been open on Saturdays since October 1893 to cater for football matches in the pleasure gardens.

Watkin's vision of Wembley Park as a day-out destination for Londoners had far-reaching consequences, shaping the history and use of the area to the present day. Without Watkin's pleasure gardens and station it is unlikely that the British Empire Exhibition

The British Empire Exhibition was a colonial exhibition held at Wembley Park, London England from 23 April to 1 November 1924 and from 9 May to 31 October 1925.

Background

In 1920 the British Government decided to site the British Empire Exhibit ...

would have been held at Wembley, which in turn would have prevented Wembley becoming either synonymous with English football or a successful popular music venue. Without Watkin, it is likely that the district would have simply become inter-war semi-detached suburbia like the rest of west London.

The tower was intended to rival the Eiffel Tower

The Eiffel Tower ( ; french: links=yes, tour Eiffel ) is a wrought-iron lattice tower on the Champ de Mars in Paris, France. It is named after the engineer Gustave Eiffel, whose company designed and built the tower.

Locally nicknamed "'' ...

in Paris. The foundations of the tower were laid in 1892, the first stage was completed in September 1895 and it was opened to the public in 1896.

After an initial burst of popularity, the tower failed to draw large crowds. Of the 100,000 visitors to the Park in 1896 rather less than a fifth paid to go up the Tower. Furthermore, the marshy site proved unsuitable for such a structure. Whether the original design (which was to have had eight legs) would have distributed the weight more evenly cannot be known, but by 1896 the four-legged tower was clearly tilting. In addition, Watkin had retired from the chairmanship of the Metropolitan in 1894 after suffering a stroke, so the tower's enthusiastic champion was gone. In June 1897 the tower was illuminated for Queen Victoria's 60th Jubilee, but it was never extended beyond the first stage.

In 1902 the Tower, now known as ‘Watkin's Folly’, was declared unsafe (though this was because of concerns about the safety of the lifts, rather than directly about the subsidence) and closed to the public. In 1904 it was decided to demolish the structure, a process that ended with the foundations being destroyed by explosives in 1907, leaving four large holes in the ground. The Empire Stadium (later known as Wembley Stadium) was built on the site in 1923.

Political career

Throughout his life, Watkin was a strong supporter ofManchester Liberalism

Manchester Liberalism (also called the Manchester School, Manchester Capitalism and Manchesterism) comprises the political, economic and social movements of the 19th century that originated in Manchester, England. Led by Richard Cobden and John ...

. This did not equate to consistent support for a single party. Watkin was first elected Liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment and m ...

Member of Parliament for Great Yarmouth

Great Yarmouth (), often called Yarmouth, is a seaside town and unparished area in, and the main administrative centre of, the Borough of Great Yarmouth in Norfolk, England; it straddles the River Yare and is located east of Norwich. A pop ...

(1857–1858), and then Stockport

Stockport is a town and borough in Greater Manchester, England, south-east of Manchester, south-west of Ashton-under-Lyne and north of Macclesfield. The River Goyt and Tame merge to create the River Mersey here.

Most of the town is within ...

(1864–1868). He unsuccessfully contested the East Cheshire seat in 1869. He was knighted in 1868 and became a baronet

A baronet ( or ; abbreviated Bart or Bt) or the female equivalent, a baronetess (, , or ; abbreviation Btss), is the holder of a baronetcy, a hereditary title awarded by the British Crown. The title of baronet is mentioned as early as the 14th ...

in 1880. He was also High Sheriff of Cheshire

This is a list of Sheriffs (and after 1 April 1974, High Sheriffs) of Cheshire.

The Sheriff is the oldest secular office under the Crown. Formerly the Sheriff was the principal law enforcement officer in the county but over the centuries most ...

in 1874.

In 1874, he was elected Liberal MP for Hythe

Hythe, from Anglo-Saxon ''hȳð'', may refer to a landing-place, port or haven, either as an element in a toponym, such as Rotherhithe in London, or to:

Places Australia

* Hythe, Tasmania

Canada

*Hythe, Alberta, a village in Canada

England

* T ...

in Kent. He increasingly moved away from the Liberal party under William Ewart Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone ( ; 29 December 1809 – 19 May 1898) was a British statesman and Liberal politician. In a career lasting over 60 years, he served for 12 years as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, spread over four non-conse ...

and in 1880 it was claimed that he had taken the Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization i ...

whip

A whip is a tool or weapon designed to strike humans or other animals to exert control through pain compliance or fear of pain. They can also be used without inflicting pain, for audiovisual cues, such as in equestrianism. They are generally e ...

. He never stood for election as a Conservative and continued to sit with the Liberals. Between 1880 and 1886, he was regarded variously as a Liberal, a Conservative and an independent

Independent or Independents may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Artist groups

* Independents (artist group), a group of modernist painters based in the New Hope, Pennsylvania, area of the United States during the early 1930s

* Independ ...

. In 1886, he voted against Gladstone's Irish Home Rule

The Irish Home Rule movement was a movement that campaigned for Devolution, self-government (or "home rule") for Ireland within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It was the dominant political movement of Irish nationalism from 1 ...

bill and was thereafter commonly described as a Liberal Unionist

The Liberal Unionist Party was a British political party that was formed in 1886 by a faction that broke away from the Liberal Party. Led by Lord Hartington (later the Duke of Devonshire) and Joseph Chamberlain, the party established a political ...

.

The confusion over his status came to the fore when he resigned his Hythe seat in 1895. The Liberal Unionists and the Conservatives were in alliance and each claimed incumbency

The incumbent is the current holder of an office or position, usually in relation to an election. In an election for president, the incumbent is the person holding or acting in the office of president before the election, whether seeking re-ele ...

and the right to nominate his replacement. Watkin for his part insisted that he was a Liberal, albeit one who had moved away from the official party. The Conservative Aretas Akers-Douglas Aretas Akers-Douglas may refer to:

* Aretas Akers-Douglas, 1st Viscount Chilston (1851–1926), British Conservative politician

* Aretas Akers-Douglas, 2nd Viscount Chilston

Aretas Akers-Douglas, 2nd Viscount Chilston, (17 February 1876 – 25 ...

commented that no one knew what his politics were, except that he had voted for anyone or anything to get support for his Channel Tunnel. The Conservatives forced the Liberal Unionists to back down and won the seat in the 1895 United Kingdom general election

The 1895 United Kingdom general election was held from 13 July to 7 August 1895.

William Gladstone had retired as Prime Minister the previous year, and Queen Victoria, disregarding Gladstone's advice to name Lord Spencer as his successor, ap ...

.

Personal life

Watkin lived at Rose Hill, a large house in

Watkin lived at Rose Hill, a large house in Northenden

Northenden is a suburb of Manchester, Greater Manchester, England, with a population of 14,771 at the 2011 census. It lies on the south side of the River Mersey, west of Stockport and south of Manchester city centre, bounded by Didsbury t ...

, Manchester

Manchester () is a city in Greater Manchester, England. It had a population of 552,000 in 2021. It is bordered by the Cheshire Plain to the south, the Pennines to the north and east, and the neighbouring city of Salford to the west. The t ...

. The family home was purchased by his father in 1832 and Edward inherited it upon his father's death in 1861.

Edward Watkin died on 13 April 1901 and was buried in the family grave in the churchyard of St Wilfrid's, Northenden, where a memorial plaque commemorates his life.

Watkin married Mary Briggs Mellor in 1845, with whom he had two children. Their son, Alfred Mellor Watkin

Sir Alfred Mellor Watkin, 2nd Baronet (11 August 1846 – 30 November 1914) was a Liberal Party politician and railway engineer.

Railway career

In 1863, around age 17, Watkin became an apprentice in the locomotive department of the West Midland ...

, became locomotive superintendent of the South Eastern Railway in 1876/ref> and Member of Parliament for the Great Grimsby constituency in 1877. A daughter, Harriette Sayer Watkin, was born in 1850. Mary Watkin died on 8 March 1888. After four years a widower, Watkin married Ann Ingram, widow of

Herbert Ingram

Herbert Ingram (27 May 1811 – 8 September 1860) was a British journalist and politician. He is considered the father of pictorial journalism through his founding of ''The Illustrated London News'', the first illustrated magazine. He was a ...

, on 6 April 1892.

Notes

References

* * * * * * *Further reading

* * *External links

* * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Watkin, Edward Liberal Party (UK) MPs for English constituencies People associated with transport in London 1819 births 1901 deaths Baronets in the Baronetage of the United Kingdom Whig (British political party) MPs for English constituencies UK MPs 1857–1859 UK MPs 1859–1865 UK MPs 1865–1868 UK MPs 1874–1880 UK MPs 1880–1885 UK MPs 1885–1886 UK MPs 1886–1892 UK MPs 1892–1895 Channel Tunnel Great Central Railway people South Eastern and Chatham Railway people Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway High Sheriffs of Cheshire Politics of the Borough of Great Yarmouth Liberal Unionist Party MPs for English constituencies Directors of the Great Eastern Railway Railway executives British railway entrepreneurs Members of the Parliament of the United Kingdom for Stockport 19th-century British businesspeople